news Australian and international cryptographers have published statements noting they remain “deeply concerned” about Australian legislation that places some controls on research involving sensitive technologies such as encryption, despite several years of consultation resulting in recent multi-partisan moves to rectify flawed legislation first introduced in 2012.

A controversial past

The Defence Trade Controls Bill 2011 was introduced in November of that year by the then-Gillard Labor administration and eventually passed both the Senate and the House of Representatives a year later. The bill’s aim was to give effect to a Defence-related treaty between the United States and Australia regarding control of sensitive technologies which might relate to the military and strategic environment.

At the time, the legislation faced extremely heavy criticism from the education sector due to its potential to enact extremely tough penalties on academics for merely carrying out legitimate research.

University of Sydney deputy vice-chancellor (research) Jill Trewhella wrote at the time, for instance, that the bill could criminalise the publication of information relating to, for example, issues as basic and relating to the public interest as pandemic flu outbreaks. “It would impede top scientists in developing technologies for tomorrow’s high-tech manufacturing industries, new vaccines and potential cures for cancer,” the academic added in an article for the Sydney Morning Herald.

The Senate Foreign Affairs and Trade Committee (FADT), in its report on the bill, made an extensive list of recommendations for improving it, while the Liberal Opposition and the Greens penned their own dissenting report recommending the “complex and flawed” legislation be further examined due to the Department of Defence’s “seriously deficient” consultation efforts on the bill.

During the Senate debate on the bill, independent Senator Nick Xenophon described the circumstances surrounding the introduction of the bill — allegedly timed to coincide with a visit by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to Australia — as “nothing short of laughable”.

Although the bill ultimately passed following a fraught parliamentary debate, a number of its provisions were not scheduled to come into force until this year, giving academics and industry breathing room to consider the legislation.

What followed was two further years of consultation about the legislation, with the Senate FADT Committee and other groups such as the Strengthened Export Controls Steering Group chaired by Australia’s chief scientist, Professor Ian Chubb and the Defence Export Controls Office, continuing to examine the legislation and ways in which it could be improved.

The result was the Defence Trade Controls Amendment Bill 2015, which aimed to fix most of the problems of the previous legislation and was passed in March this year after a brief debate, following a public consultation which kicked off late in 2014.

Unlike its previous iteration, the 2015 bill received few complaints from Australia’s education sector or industry. Universities Australia, in its submission to the FADT Senate Committee on the bill, wrote that it addresses “the major concerns raised by the university sector” and advocated for the bill to be passed. The FADT Committee, in its latest report on the bill, noted:

“… it is apparent to the committee that the amendment bill enjoys broad support, particularly within the academic and research community, who believe it has resolved many of the issues which so troubled them in the original Act. Even those who retained serious concerns about aspects of the legislation were mostly supportive of the passage of the amendment bill, observing that it improves upon the provisions of the Act, and will extend the transition period to address ongoing issues.”

New complaints

Despite the broad consensus about the improvements to the original Defence Trade Controls legislation and its extensive consultation period, over the past several weeks, new voices have started raising complaints about the legislation.

As first reported by iTnews, last week the International Association for Cryptologic Research published a petition from 183 cryptographers located globally, including a half dozen from large Australian universities, expressing the fact that they remain “deeply concerned” about the Defence Trade Controls Act. The petition states:

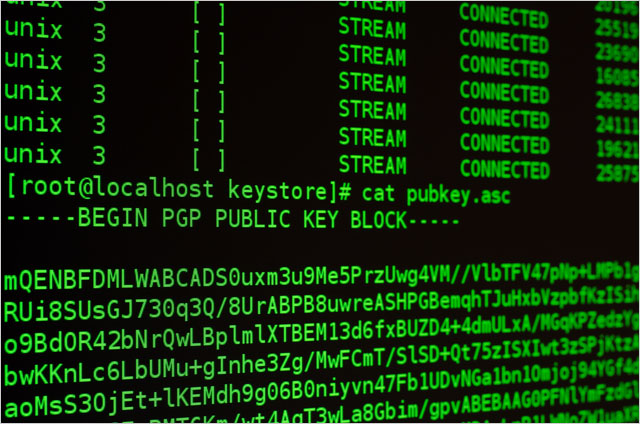

“The act prohibits the “intangible supply” of encryption technologies, and hence subjects many ordinary teaching and research activities to unclear, potentially severe, export controls.

As an international organisation of cryptographic researchers and educators, we are concerned that the DTCA criminalises the very essence of our association: to advance the theory and practice of cryptography in the service of public welfare.”

“We affirm that the public welfare of Australians — and society in general — is best served by open research and education in cryptography and cybersecurity. Open, international scientific collaboration is responsible for the encryption technologies that are now vital to individuals, businesses, and world governments alike. The current legislation cuts off Australia from the international cryptographic research community and jeopardises the supply of qualified workforce in Australia’s growing cybersecurity sector.

We call on Australia to amend their export control laws to include clear exemptions for scientific research and for education.”

And in mid-May, Manoash University mathematics lecturer Daniel Mathews penned an article for The Conversation, stating:

“There is nothing wrong in principle with government regulation of military technology. But the net is cast too broadly in the DSGL, especially in the case of encryption. The regulatory approach of the DTCA’s permit regime is effectively one of censorship with criminal penalties for breaches.

The result is vast overreach. Even if the Department of Defence did not exercise its censorship powers, the mere possibility is enough for a chilling effect stifling the free flow of ideas and progress … the laws remain paranoid. The DSGL vastly over-classifies technologies as dual-use, including essentially all sensible uses of encryption.

The DTCA potentially criminalises an enormous range of legitimate research and development activity as a supply of dual-use technology, dangerously attacking academic freedom —- and freedom in general —- in the process.”

Opinion/analysis

There’s been a lot of concern out there over the past few months about the various pieces of Defence Trade Controls legislation, so let’s get the black and white stuff out of the way first, so that we can understand what we are talking about here.

Firstly, there is no doubt that the original Defence Trade Controls Bill 2011 introduced back in 2010 was terrible. The then-Labor Government barely consulted about the bill, resulting in a horrendously rushed parliamentary process where even the Government’s own Senators expressed substantial concerns about it.

This is what happens when you let the United States set foreign policy for Australia, aided by bureaucrats within our own Department of Defence — the rest of Australia gets left out of the picture.

It is just as obvious that the new Defence Trade Controls Amendment Bill 2015 does a lot to clean up this mess. Australia’s university sector is broadly happy with the revised bill, and virtually no complaints were raised about it in the three month window between its exposure draft being published and the bill being passed.

So what are we to make of the belated complaints by cryptographers that the Defence Trade Controls Act is still unworkable? Personally, from what I can see, I do not expect the bill to “criminalise” the teaching of encryption, as Monash University Daniel Mathews has claimed. I don’t expect Defence to be locking up mathematicians of any stripe, and I certainly don’t expect consumer or business use of encryption to be affected at all.

What I think we’re seeing here is the inevitable and ongoing subtle back and forth tug of war between the Government, which wants total control over any sensitive technology, and academics, which naturally want academic freedom.

The bill as amended probably, as Mathews notes, constitutes some degree of “overreach”, and its theoretical implications are onerous. Not surprising, given how conservative Australia’s two major political parties are about national security matters. But in practice I don’t think it will change much in the real world in terms of how academics and industry uses and researches encryption. It will probably result in a few back-room conversations between really top-end encryption researchers and Defence occasionally — but then, those conversations were probably happening anyway.

If the bill does have the drastic implications that researchers fear, I suspect we’ll hear about it immediately in the form of lawsuits from either side. But my gut feeling tells me we won’t.