news A number of global technology vendors likely to be hauled before Australia’s Parliament to justify their local price markups have grudgingly and briefly signalled their acceptance of the proceedings and willingness to participate, although some have completely refused to comment on the issue.

In late April, Communications Minister Stephen Conroy confirmed the Government would hold an official parliamentary inquiry into the issue of technology companies marking up goods and services for Australia, following a long-running campaign by Federal Labor MP Ed Husic.

Husic (pictured right) has been raising the issue in Parliament and publicly since the beginning of 2011 (he was elected in the 2010 Federal Election), in an attempt to get answers from technology giants such as Adobe, Microsoft, Apple and others as to why they felt it was appropriate to price products significantly higher in Australia (even after taking into consideration factors such as exchange rates and shipping) than the United States.

Just last week, for example, global software giant Adobe continued a long-running tradition of extensively marking up its prices for the Australian market, revealing that locals would pay up to $1,400 more for the exact same software when they buy the new version 6 of its Creative Suite platform compared to residents of the United States.

After the inquiry was announced, Delimiter invited global vendors Adobe, Microsoft, Apple, Lenovo and Amazon, which are some of the most visible companies selling high-profile technology goods and services to Australians, whether they would commit to attending the parliamentary inquiry if invited, and whether they had any other statement to make on the matter.

The results were brief.

“Adobe Systems will co-operate with any parliamentary inquiry as required,” said an Adobe spokesperson. “We are not making any further statement at this time.”

Microsoft is charging Australian software developers about 83 percent more than their US counterparts to access subscription services associated with its Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN) platform, and also charges higher prices for software products and cloud computing offerings.

A spokesperson for the Redmond, US-based company said: “Microsoft will review the Parliamentary Committee’s terms of reference when available and will respond to the Inquiry.”

Lenovo and Amazon are both represented in Australia by the public relations agency Text100. The company acknowledged the receipt of queries on the matter of the price inquiry, but did not respond with comments on the matter. Spokespeople for Apple did not acknowledge the receipt of Delimiter’s queries and did not issue a comment on the matter.

PC manufacturer Lenovo has in the past attempted to defend of its Australian pricing, despite in 2011 launching its flagship new ThinkPad X1 laptop in Sydney for$560 more than the same hardware will cost in the United States. Apple also commonly charges more for its products in Australia, although the company has made some moves towards international price harmonisation over the past year. Amazon’s prices are the subject of less complaints by Australians than the other vendors mentioned in this article, but price differences on the company’s extremely popular eBooks offerings do exist, despite the content being the same between jurisdictions.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), which has indicated that it is following the issues the IT price hike inquiry is raising, is also interested in the eBook issue. In mid-April, the regulator noted it was considering its options on the issue of eBook pricing, following a lawsuit filed by the US Justice Department against Apple and five global book publishers on the issue of price fixing.

opinion/analysis

I am disappointed in the muted reaction which we’ve seen from these massive technology vendors on the issue of IT price hikes in Australia so far. This is an issue for the entire technology sector to ponder, and we really need these companies to be open and honest about how they set pricing so the debate on the issue can be on an honest grounding.

It is possible that the parliamentary inquiry approved by Conroy will broadly find that vendors such as Adobe and Microsoft have been doing nothing wrong when it comes to their Australian pricing, and that their honest testimony will vindicate their actions. We need to keep an open mind with respect to this possibility. But the unwillingness of the vendors to comment on the issue will only lead to an impression that they have something to hide.

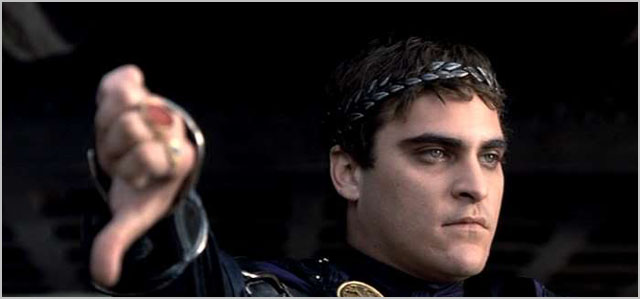

Image credit: Still from Gladiator

“It is possible that the parliamentary inquiry approved by Conroy will broadly find that vendors […] have been doing nothing wrong when it comes to their Australian pricing”

Strange, I didn’t think Delimiter was a comedy website? ;-)

… in all seriousness though, I’m very interested in hearing the reasoning behind the price differences that will hopefully emerge from this inquiry (beyond the loose “free market” excuse or “cost of providing support”, both of which are pretty flimsy). I know there’s some differences in terms of tax levels and the like, but certainly not of the magnitude of the many hundreds of dollars of difference we see on way too many products – especially digital ones with no physical postage/delivery cost.

This is a ridiculous bit of posturing from Ed Husic designed to get his head on the telly, and nothing else.

Software costs more in Australia for the exact same reason that cars, clothes, a pint of beer, shoes, TVs, food, a 3bh house near the beach, and a cup of coffee all cost more – because people make more money.

You don’t need a parliamentary inquiry to tell you this. What will Husic do with the results of his inquiry? Is he going to enact ceiling price legislation? Of course not. Why is he doing this again?

But it hasn’t aways been that way, Australians making “more money” than Americans is a relatively new phenomenon – we’ve still always paid through the nose for IT product.

In fact, even for 2011, the purchasing power parity of the US was at 31,111 whilst Australia was at 26,915 – suggesting that the “we make more money” excuse is a bit of a furphy – especially seeing as the dollar was quite strong at that time.

“but price differences on the company’s extremely popular eBooks offerings do exist, despite the content being the same between jurisdictions.”

Isn’t this the fault of the publishers, not Apple?

I hope they really delve into this. It will open a whole can of worms on why goods cost more in Australia. Sure, some of it is the manufacturer/developer, or at least the manufacturer/developer under pressure from the local supply chain. I hope they dig this up and make it public. If they find the cause is local suppliers/wholesalers they better out them. It’s about time the whole filthy Australian wholesaler/importer network lost some of their stranglehold on companies who develop goods and those that retail them.

Best of luck to Husic.

He’s going to step on a bunch of toes, and egos, for no real gain. He, and by extension the Party can’t “do” anything about it without legislative changes; they’re not in power so at best can, well, complain a lot.

There’s also the tax equation, along with import duties and a raft of other factors that also need to be considered; they likely won’t be, of course, so that leaves a narrow frame of reference.

Brendan, which import duties are you talking about?

There are none on software & hardware (as I understand and according to the ATO website) nor have been since the introduction of the GST.

Why do people keep raising this non-existant issue?

Possibly because it’s the Customs Office that handle import duties?

http://www.customs.gov.au/site/page4368.asp

ATO manages Australian Taxes, Customs look after Import and Export excises, etc. AFAIK.

Excellent and where are the duty rates for hardware and software?

Oh, here we go:

The Duty rate on computers/parts/software is free (0%) as stated in the

Australian Customs Tariff. It will attract 10% Goods And Services Tax (GST).

So still no duty….

Even the transport costs are a bit of a furphy. These goods aren’t coming from the US. They are coming from Asia in the main.

The price issue isnt necessarily a comparison directly between Oz and the US. We understand that a large portion of things arent made in the USA, but Asia – which is closer. However to products that are sold and applied digitally, what excuse is there ? None.

Theres No or very minor logical reasons as to why a digital product would see a price change, other than perhaps GST. Given there is no box, no manuals and no extra “Gifts with Purchase” – theres no logical reasons. Digitally , you’re using your own connection to do all the work for exactly the same product as our American friends.

I do know why some of the digital prices are higher here. It is where a downloaded product is also sold on store shelves. I have had several games where the digital price needed to be raised to closer to the store price or the distributor would simply not take products off the publisher and sell them to the shops. Unfortunately it’s blackmail that is effective as still most games are sold through stores.

It is also against the law for one entity to tell another how to set their prices.

I don’t really blame the wholesalers although by accounts they are likely to be the direct reason for the high prices. The wholesale price I get for some of these goods here is higher than the street price in other regions and if the manufactures is to be believed they are selling at the same price to all markets. I know some larger companies in Australia who are able to bypass the Australian wholesalers occasionally have been selling at less than the Australian wholesale price.

The issue is with manufactures restricting wholesalers and retailers from selling outside their region into other markets, this means the Australian Wholesalers don’t need to compete internationally. The wholesalers make ever increasing margins as the dollar increased which more than offset their loses from slightly reduced volume due to gray imports. The only people who lose out are the retailers who don’t see the benefit of increases in the dollar on their price of goods but do see the lost sales and the consumers, who are losing out on local support when they look for truly competitive prices or are paying higher prices.

Despite what some people suggest gray market importing isn’t always easy due to the restriction placed by the manufactures. Some of the recommendations for bypassing those restrictions can be considered fraud.

“The issue is with manufactures restricting wholesalers and retailers from selling outside their region into other markets”

Part of that is pressure from the wholesalers. They wan’t exclusive rights to sell the product in that territory. You think the manufacturer gives a damn what region you buy from?

Why do you think wholesalers care what region their retailers sell products in?

While both large and small retailers might want exclusivity in a market they generally don’t want it at the expense of having their market restricted.

Exclusivity is hammer wielded by both parties.

Wholesalers like it because it helps them maintain margins, manufactures like it because it help them keep a tight rein on the wholesalers. The threat of lose of exclusive right to certain products can drive up sales in a region without bleeding sales from another region, and is a tool wielded by both manufactures when dealing with their vendors and vendors when dealing with retailers.

Wholesalers have a tight rain on the manufacturers in Australia. See my post down lower, Australian wholesalers force the hands of various brands to push prices up they won’t take their products.

That is not the case with all brands and models.

If you are a new manufacture then the wholesaler can be a impediment to the growth of business in a region.

But say you are a supplier for a company the likes of Apple, being the apple supplier will drive retailers to you as they want access to the Apple products. If apple is happy with you supplying their product either because of street price the product end up at or advertising and support you offer you risk losing a lot of business as a supplier if apple withdraws.

I’ve seen it happen in other retail sectors with one big name in the sector withdrawing their brand from a sizable supplier because the terms the supplier was giving to retailers was slowly turning their brand from an Apple into a Compaq. The big issue with the IT supply sector is it seems to be too reliant on a couple of large channel partners with exclusive contracts, and only the biggest of retailers are able to “offend” those channel partners by going elsewhere for other products where possible.

The problem is though, if you withdraw your brand from the supplier how do you get it to them? Direct? Fine. Will the retailer be punished by the supplier they bypassed on the other products they supply them with, you bet.

Another issue with going elsewhere for supply. I think a lot of Australian retailers are just too lazy to do that. They get supplied by these wholesalers/importers, most of which try to tie then source up with exclusivity. The exclusivity works on a lot of products, obviously not Apple, etc. But it does mean a hold over the retailers. I think a lot of Australian retailers have been using this method of supply for so long they just keep using it, don’t import themselves. It would be a hard job to do all the supply internal, because once you start bypassing the local “cartell” you probably will have to do it for everything you sell.

It does not surprise me in the slightest that these companies have clamed up when asked for comment, because what the hell are they supposed to say? How can they justify their actions? The simple answer is they can’t.

This is the first time a Government has had the balls to call this rorting into question, and now that they have made their intentions clear, the companies don’t know what the hell to tell people, because they HAVE been rorting Australians and they damn well know it, and I hope this inquiry publicly shames them to hell and back. They’ll quickly bring their prices in line when the bad press rolls in.

Will be interesting to see how Microsoft can justify 83% markup on a product just to hire some sales and marketing droids, particularly when the products original cost (in the USA) includes development, distribution, support, profit margin and yes… sales and marketing droids.

Good place to be when a tiny and somewhat unimportant part of the chain can decide it’s worth an extra 83% over the rest of the company :/

Lol, I agree with there is little reason for MSDN to be more expensive. You may want to look up what it is though :)

Hmmm, I just noticed I have a subscription to both Professional and Ultimate. I better check someone hasn’t made a very expensive mistake.

Phew, one was just an old non active subscription being listed.

Standover merchants always hate it when somebody wants to bust up their cosy little market in extortion.

Not that any of the multinationals would ever think of doing such a thing. Goodness me, no.

I was considering getting a 1st generation Ultrabook, until I realised the prices I was seeing were for customers in the US, and when I changed to the AU site the prices went up by $400 – $500, which was 40-50%.

In regards to the prices of computer games and software, it would be interesting to research how loudly Adobe whinge about their products being ‘file-shared’, and though it’s not a complete justification for not paying for the product, it gives the end user (notice I didn’t say customer) a sense of satisfaction to give the two-fingered salute to what they consider to be a ‘greedy corporation’.

Here’s a link from another Delimiter article that has some supposed justifications for Office 365 being more expensive in AU than in the US:

http://thecloudmouth.com/2012/04/19/explaining-the-higher-cost-of-office-365-in-australia/

I can probably give you a fairly good idea of the causes for this pricing disparity, although nothing I have to say is anything new.

Let’s sart with the manufacturer – for a given product (under normal market conditions) the more units you manufacture the lower the cost per unit. That’s called economies of scale, a simple and fundamenal economic concept.

When that manufacturer goes to sell that product, they want a number of things – they want to sell at the highest possible price the market will bear, they want to sell as many units as possible, to the smallest number of customers to simplify and reduce the costs of shipping, inventory, manufacturing, forecasting and aftersales service and support. In order to strike the best compromise between these competing goals, manufacturers will usually enter into binding legal agreements with key distribution partners (and sometime very large retailers) which provide benefits to these distribution partners such as market exclusivity in their region, while the manufacturer simplifies sales, account management, logistics and support, streamlines everything from manufacturing forecasting through to end user support,and all these efficiencies lead to dramatic cost reductions.

The other cornerstone in the wholesale pricing model is, of course, the tiered volume pricing structure. Basically, the more units purchased in a single order, the lower the price per unit. For example, a manufacturer may sell product X for $90 in 1,000 unit quantities, but $80 in 10,000 unit quantities, and $65 in 100,000 unit quantites. It makes a lot more per unit in smaller quantities, but the costs of logistics and support are greater for smaller quantities. Larger orders also give the manufacturer greater confidence and stability, enabling them to manufacture more units per order, and purchase assembly components in greater numbers (giving them lower costs per unit), all of which reduces the cost of manufacturing each unit.

Bear in mind that ‘large’ distribution partners for the Australian region (who may well have a monopolistic ‘exclusive distribution’ agreement) may be buying less than 10% of the volume of major American retailers like Walmart. Superdistributors like Ingram-Micro account for much larger volumes as they distribute to multiple regions and countries, but they introduce their own problems (monopolies by definition have no competition thus they are free to set prices at whatever level they choose).

So, that’s the first part of the problem – Australian distributors simply can’t compete on unit volume, thus they pay more per item, so even with the same margin, it costs more at retail.

In specific regions manufacturers and distribution partners are traditionally quite sensitive to retail pricing ramifactions across the market, which is where the ‘MRP’ or ‘RRP’ comes in – small retailers can still make a modest profit (around 3% in the cut-throat consumer IT space) while huge conglomerates that control the whole supply chain to retail end up with inflated margins per unit – everyone’s a winner (or so the philosophy goes). However, if you have a large, powerful retailer who engages in agressive tactics against their competition, they can set their pricing at a modest markup over their (heavily discounted) cost price per unit, which results in a retail price lower than the cost price to their competitors. So now your RRP means nothing and the smaller retailers either keep trying to sell the same item with a higher price (not too hard if you differentiate your ‘brand’ with other things like customer service that the large retailer can’t match), or they try to match the discount price on some items in the hope that it will keep bringing customers through the door, but they’ll be able to sell them other items with more reasonable markup. Such predatory pricing usually results in the collapse of the smaller businesses. If we’re using the Internet to determine the internationally available cost of a product, we may be seeing the extremely cheap pricing of low margin, large volume retailers, which even most US retailers can’t compete against.

But that still doesn’t explain why the RRP on an item is so much lower in the US than Australia, regardless of real world discounted shelf prices.

I’ll illustrate the next part of the story with a fictional example. An Australian distributor buys product X for a wholesale, before tax cost of $80, while in the US it retails for $150 (I’m being generous – that’s a pretty huge markup for the US). The wholesaler is already buying this product for 10 to 20% more than large US companies because they are buying for a potential market of 400,000 people in a population of 22 million, compared with a potential market of 5.8 million in a population of 330 million. Now their $80 item has cost them an additional 5% import duty (I have no idea what the previous comment above was about – there is almost always 5% duty on any non-special good imported to Australia. Special goods attract much higher duty) and 10% GST, for a cost of $92. Plus they’ve had to ship the item, but assuming they use 40′ containers that cost may be less than $1 per unit, averaged out. So let’s say we’re at $93.

Now we get to the elephant in the room. Where in some countries where competition is fierce, life is hard, and where there is no minimum wage but if there were it would be a few cents per hour, businesses apply a markup that the market can bear and that they can survive with given a strong competitive environment. Australian people and Australian businesses don’t operate like that. Because major distributors in Australia are often the ONLY authorised distributor (or one of few) they set their margins very high. We’re not talking 5 or 10%, more in the range of 20 to 40%. The next step may be to retailers, but more often the ‘distribution partner’ or importer is only the conduit into the country. They then sell to wholesalers (who may then sell to ‘resellers’), who then sell to retailers. Every step in this process prior to retail adds 20 to 40% (on average) without adding any additional value. Retail margins vary wildly, depending on the product. Consumer hard disk drives, for example, are extremely price sensitive, so are often ‘loss leaders’, sold literally at a small loss just to get customers in the door. If the retailer is happy to charge higher prices than the discount competition, their markups are still often 3% or less.

As an aside, this is where parallel imports come in – a small player will go to another region with cheaper prices and buy products in bulk for far less than they’d pay to the ‘authorised’ Australian distributor, stick everything in a container and bring it over for direct sale at the retail level. These products don’t have normal channel warranty, so you have to take them back to the store of purchase for warranty claims, which may take them months to resolve (as they process warranty like they import – in bulk, so your product will sit around until they have a whole container of warranty products to return). The upside for consumers is access to products well below the price other retailers can sell them for, while the parallel importer has vastly greater margins than they would have buying through a local distributor, while consumers pile through their stores in droves to get access to the cheap, ‘below cost’ items.

The further you get away from the budget consumer space, though, margins are much more palatable (for the retailer, at least). Retail markups to RRP on mid range computer hardware usually sit between 10 and 20%. Premium computer gear may have markups of up to 40%.

Then you get to ‘professional’, business and enterprise IT. Products for the small to mid business space may actually have quite low margins, in the 10-20% area. But it can depend a lot on the product category – printers and photocopiers, for example, often have 30 to 40% margin built in (the photocopier channel is very tightly controlled by vendors, so while there’s competition between major brands, there is zero competition between different businesses selling the same brands in the same region. And we all know what monopolies do to the price of goods…).

Enterprise and government sectors are (of course) where the real money is. One major brand at the centre of this new enquiry, for example, used to have markups of over 100% for some of their enterprise licensing suites in 100 EUL bundles. The markups on everything from HDDs to servers, racks to switching equipment, cable to software licenses in the enterprise space is breathtaking. This is why getting on the shortlist as an authorised supplier to Govt is a license to print money – without adding any real value and while only having to compete with two or three other competitors (with whom you’re probably quite friendly) all you have to do is fill orders from non-discerning govt purchasing offices with budgets far in excess of their annual requirements (who are actually desperate to spend as much as they can on as little as possible every year, just prior to the next round of funding, because if they don’t spend their whole budget, it will get cut for the following year).

To be perfectly honest, I think this is where you’ll find the cause of the price disparity between products in Australia and in other markets such as the US – Australians are greedy and they have a culture of entitlement. They feel it is their right to be a millionare, and every sale should propel them noticably closer to that goal. It doesn’t matter that they’re selling a product that took the engineering expertise of thousands of people over many years to produce, they feel that it is their right to make at least 50% – after all, the Govt gets 10% for doing absolutely nothing, right? Add together a lot of people in a supply chain with this mentality and the cost of good blows out pretty fast.

So let’s go back to our fictional model, product X – we started off with a cost price from the manufacurer of $80, which turned out to be $93 landed in Australia. That importer adds 40% markup, plus shipping (say $10). So now we’re at $140.20 by the time it’s at any large retailer (smaller retail stores will probably have an additional middle-distributor involved). This is your big departmment stores like Myers and Harvey Norman, or large specialists like JB-Hifi. Stores like this will have somewhere between 20 and 40% final retail markup, taking the realistic retail price of product X to between $168.20 to $196.30. Now a 25% markup doesn’t look great, but when you compare it to the real world street price, the disparity suddenly becomes enormous – a US retailer purchasing product X in 10,000 unit quantites at the same price as our distributor may be selling directly into the market at cost + 20%. That’s $96, less than half the shelf price of the same item in Australia, and still allowing for a reasonable margin for the discount retailer.

So how is this relevant for electronically distributed software that doesn’t pass through a physical distribution chain? Relationships. There is no major software vendor that sells products electronically that doesn’t also sell physical media and licensing through channel partners (ie the standard distribution chain). If there are physical copies of a product available in a region, the manufacturer will never deliberately and knowingly undercut the RRP on that product, even though none of the costs of distribution are involved. In fact, the manufacturer probably loves this arrangement, because any direct-to-retail sales they have in this way have astronomically huge margins.

When it comes to digitally distributed products with no physical retail-store analogue, the importers, suppliers and distributors have a voice at the negotiation table with the manufacturer. They will argue that related products must match the pricing model for the rest of the industry. So, for example, you have Microsoft selling Windows 7 Anytime Upgrade licenses (which are just an ‘unlock’ license key to enable more features; there is no actual software delivery involved) for AUD$199, while in the US the same thing can be bought for less than USD$100. Interestingly, physical boxes containing these upgrade licenses are available in stores in the US in addition to direct purchase from Microsoft, but they can only be obtained digitally, directly from Microsoft, in Australia.

So why isn’t everyone simply purchasing these products directly from the US, if they’re so much cheaper? The high-technology sector has a number of ways to ‘combat’ this behaviour. First, they limit support to the sales region. That means if you bought a laptop in the US, you would have to send it back to the US for warranty and support. In some cases, the fact that you’re a resident of another region may be enough for them to reject your support request altogether. Asus are a manufacturer that remains a noteable exception to this practice, supplying all products with an effectively unlimited international warranty, so any Asus product can be returned to any local authorised Asus repair centre for warranty support.

Some premium and enterprise products also come with ‘on-site’ support provisions, so if you have a support issue a technician will attend your location to repair or replace the faulty product at no charge. This argueably high value service is worthless if you’re outside the prescribed support region.

Then there is operation of the product – some products simply won’t work once they detect they are outside the prescribed region. DVDs and Blu-Ray films are an obvious example, but there are plenty of other devices and software that cripple themselves in a similar fashion. The smarter the device the smarter it can be about controlling your use of it, too.

This is why all the key vendors in the spotlight over this issue are both nonplussed and surprised at the attention – to them, this is business as usual, none of this is new, none of it is unknown and none of it is in any way illegal. This is the natural market of capitalism at work – companies and individuals who have a vested interest in maximising profits by definition. To combat it you’d have to flatten and broaden the supply channel and create a paradigm shift in the fundamentally greedy, entitled and exploitative nature of Australian businesses and individuals. Good luck with that.

There is a silver lining to this, in a limited sense. It provides opportunities for innovation for people and businesses willing to think (and work) outside the box. The best example of this that I’m aware of is Kogan – they have essentially replaced not only the distribution channel to retail, but also the vendor – the only part they don’t ‘own’ is physical manufacturing, and almost no vendor ‘manufacturers’ these days manufacture in-house in 2012, anyway. Kogan uses the same factories that produce products for vendors from Samsung to Sony, but their products only have a single stop between the manufacturing plant and the consumer (and with their innovative ordering system, even that stop is almost completely redundant for many of their orders now, too). They have a single (quite reasonable) markup, so they are highly profitable while undercutting nearly identical products from other brands by 50 to 70%. What Australia needs are more innovative companies like this, but unfortunately that means a lot of existing, less efficient businesses will fail, with a knock-on effect of high unemployment (not just distributors going out of business, but all the brick-and-mortar retailers, too).

What this shows us is our current retail business environment is unsustainable, but most Australians from store owners to distributors to politicians aren’t prepared to even consider this yet, let alone accept it.

Here is the same thing happening in the fashion industry. Australian importers pushing to stop brands selling to Australia from overseas. They are doing so by getting those stores to raise prices or they stop importing some brands.

http://au.lifestyle.yahoo.com/fashion/features/article/-/13660470/online-shopping-prices-set-to-rise/

Yep, it happens in almost all industries, and that is what really needs to be looked at, it should be law that companies in Australia can buy from companies in the US at the exact same rates that US companies purchase them at.

We have a FTA, if they don’t want this we should rip up the FTA, we got screwed on it anyway, all that happened was protectionist policies that made governments money (to spend on infrastructure) were removed, and the companies said, “oh thanks, we’ll take money”, and erected (or continued) their own.

Comments are closed.