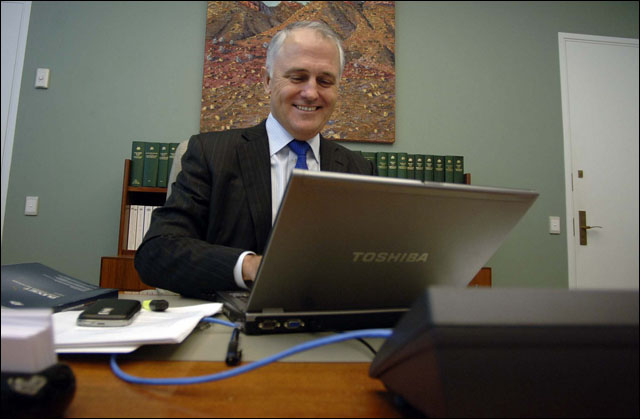

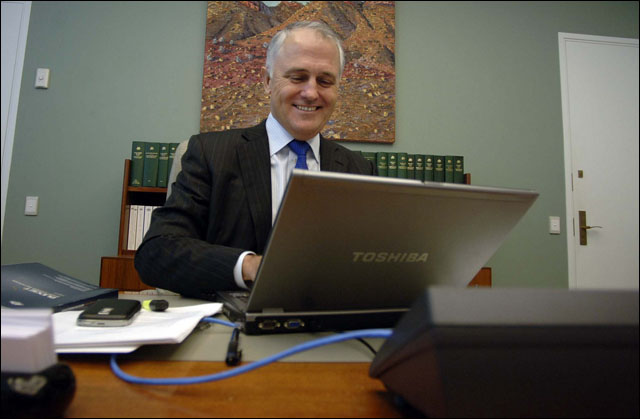

This article by Communications Minister Malcolm Turnbull first appeared on Delimiter in October 2010, shortly after Turnbull was appointed Shadow Communications Minister. Delimiter re-prints this article today for the edification of readers, in light of the news that Turnbull has approved NBN Co to go ahead with the controversial ‘Multi-Technology Mix’ option for its broadband rollout, despite the fact that the cost/benefit analysis being conducted into the project will not be completed until the middle of 2014.

opinion Two of the biggest mistakes you can make with infrastructure are to build massive new projects on over-optimistic estimates of demand and to neglect ongoing maintenance and upgrades of your existing infrastructure assets.

Unfortunately for the taxpayer, politicians are particularly prone to making both of them. Attracted to glamorous ribbon-cutting opportunities, politicians love investing taxes in big new projects. And if anyone says “cost-benefit analysis”, it is brushed away with a call to “nation-building”.

Neglecting ongoing maintenance and investment enables governments to increase their dividends and keep the prices lower until the day of reckoning when systems start to fail and massive reinvestment is needed.

The NSW Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal has noted that real household prices for electricity and water remained below their 1993 levels until 2005. And dividends remained high, too. It was a win-win. Until it wasn’t. But the upshot of these years of neglect in water and energy infrastructure is not just higher utility bills, but bills that are higher than they would have been if the infrastructure had been planned and built in a more considered manner.

So what can we say of the cost/benefit analysis-free $43 billion National Broadband Network — the largest single infrastructure project in Australia’s history?

Does the network represent the most productive possible use of these resources? Will it earn even the paltry return on taxes invested that the government forecasts? Could the underlying objective, to guarantee universal fast broadband across Australia, have been achieved far less expensively? Will it stifle competition?

And if the NBN is the answer, what was the question? Given millions of Australians already have access to high-speed broadband and the public debate has been how to ensure all Australians have that access, why has the government failed to investigate what the relative cost of upgrading our existing telecoms network would be as opposed to trashing it and building an entirely new one?

If 100Mbps of bandwidth to every home is the answer, why does the national scheme involve shutting down and overbuilding the Telstra and Optus cable network, which passes about a fifth of Australian homes and is capable of providing that speed already?

And the cost does not stop with the government. NBN Co is not able to tell us what the cost of rewiring a house will be to enable access to the new optical fibre network. It may be worth it for those who want more bandwidth and can afford it, but for many people it will be seen as either or both an unnecessary or unaffordable expense.

But right now, that fundamental question goes unanswered.

And how convincing can any business proposal be that assumes near-universal market penetration and pricing that would result in average prices increasing when, to date, they have been declining? Most importantly, how can we answer any of these questions in the absence of the detailed cost-benefit analysis the government refuses to undertake?

The most frightening aspect of the government’s approach to the NBN is that this is a notoriously difficult area of investment. The private sector has made shocking errors in forecasting costs and matching these against future demand. Consider the $5 billion or so of private money lost in Australia since the 1990s on botched investments in motorways and tunnels such as Sydney’s Cross City Tunnel.

Similarly, private telecommunications firms burned through about US$22 billion of their shareholders’ capital during the 1997-2002 speculative investment bubble in submarine communications cables — new links that were later sold for cents on the dollar.

And there are plenty of local examples. The Optus HFC network and the Nextgen fibre optic network saw investors lose billions. So why is the government so confident it can get the network right without any rigorous analysis at all?

Most infrastructure assets endure for decades. Much of the capital spending for infrastructure is ”lumpy”; at periodic intervals, large investments have to be made to replace ageing assets or to greatly increase capacity to provide for future demand growth. The challenge is to get the timing of these lumps just right so that new capacity comes smoothly on stream just ahead of demand.

The Gillard Government must urgently undertake a thorough cost-benefit analysis of the network. Its stubborn failure to do so can only lead us to conclude that it does not want to know what that analysis will reveal.

Image credit: Office of Malcolm Turnbull

That final para is so apt. Replace just one word, and it’s a perfect description of what’s just happened today.

I don’t think so. I think Turnbull has made it abundantly clear he’s capable and willing to fiddle with and/or ignore any analysis in order to get the results he wants.

Ok, then replace one word, and add “us” between “want” and “to know”.

Should probably add “honest” after thorough, as well, to avoid the situation with the Strategic Review.

in that sense it has parallels to Abbott’s ironic article from The SMH about new governments attempting to “bully” the new opposition into submission on policy by claiming “mandate” – check it http://www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/promises-to-keep-in-opposition/2007/12/04/1196530675473.html?page=fullpage

in both cases, unadulterated opportunism

De Ja Vu..

Wow, just wow

This article should be linked to everywhere, by everyone. Social media, comments pages of IT industry sites, letters to the editor etc.

NBN switch without analysis about ‘getting on with it’: Turnbull

http://www.zdnet.com/nbn-switch-without-analysis-about-getting-on-with-it-turnbull-7000028231/

Notice his laptop is wired and not wireless… a bit hypocritical seeing outback towns which had their centres within the fibre rollout plan removed and only the surrounding areas are apart of a fixed wireless plan. I guess our primary producers aren’t respected enough by the liberals to be apart of the fibre NBN. See http://www.mynbn.info/map

I find this highly amusing, it’s sort of like watching Malcolm punch himself in the face a few times :o)

It also makes me wonder why we keep electing people so disconnected from “average” Australian’s…

Comments are closed.