opinion/analysis by Renai LeMay

12 November 2013

Image credit: Stock

NBN Co’s Strategic Review process gives the company an unmissable opportunity to re-evaluate the early decision to deploy its FTTP network primarily through Telstra’s underground ducts. The company and its new Coalition masters must now seriously consider deploying more fibre aerially on power poles in an effort to speed up its rollout substantially.

Right now, opinion is divided in Australia’s technology sector as to whether the Strategic Review process which NBN Co is currently undertaking is a serious initiative which will thoughtfully re-examine the project with a view to resolving its many problems, or whether it is merely destined to create the polite fiction that the Coalition Government is open to considering alternatives to its preferred Fibre to the Node rollout strategy.

If you believe the latter — and there is certainly significant reason to do so, given the nature of the appointments which Malcolm Turnbull has made to support the initiative, as well as the Communications Minister’s ongoing statements favouring a FTTN rollout — then the entire Strategic Review process is not worth engaging with at all. It’s nothing more than a sideshow, played out to placate the public while Turnbull and his colleagues make the real decisions behind the scenes.

But if you believe the former, then NBN Co’s Strategic Review represents a real opportunity for the company to start thinking outside the box for the first time in its existence.

Long-time critics of the NBN have pointed out that many of the company’s problems can be traced back to the dogmatic insistence of the project’s founder, then-Communications Minister Stephen Conroy, on a universal Fibre to the Premises rollout model. That decision locked out NBN Co from using Fibre to the Basement solutions in apartment blocks, it locked the company out of following the quicker and easier Fibre to the Node model which had already been proposed in Australia multiple times, and it locked NBN Co into a long-term pattern of laborious infrastructure construction which has bogged down its rollout efforts.

Conroy’s choice of the model was fundamentally based on two lines of reasoning.

Firstly and most obviously, FTTP is technically the best and most future-proof broadband technology available. If you’re going to deploy a national broadband network that will probably be in service for at least the next century, you had better use the best method available.

However, secondly, choosing the FTTP model would also allow the Government to ensure the structural separation of Telstra’s wholesale business from its retail business, removing a key conflict of interest roadblock which has long bedevilled the industry’s operations and development.

The genius of Labor’s plan was that this wouldn’t occur through separating Telstra, as other countries have done with their incumbent, but by completely overbuilding Telstra’s copper network and making it irrelevant. Conroy and NBN Co sweetened the deal for Telstra by inking a major contract to pay the telco to bring its customers onto the NBN’s new fibre infrastructure. As a side benefit, NBN Co would gain access to Telstra’s underground duct, pit and pipe infrastructure to deploy the new fibre cables through.

At the time, the whole arrangement sounded perfect. Telstra would be separated from its network operations; NBN Co would build a national fibre network to replace the copper, and all of this would be paid for by the monthly broadband plans of grateful consumers, who would for their part receive fundamental broadband service delivery improvements.

But in hindsight one little fact has gotten in the way over the past four and a half years since the NBN project was initiated: Constructing the network has proven much harder than expected.

It seems logical — so logical! — that if you’re going to deploy a fibre network around Australia, then the best way to do that is to pull the new fibre cables through the same ducts where the old copper cables still lie.

However, in practice, that process has proven to be something of a nightmare. Telstra’s ducts constitute an incredibly complex network of buried tunnels, clogged with existing decaying copper cables and packed with dangerous asbestos. Getting NBN Co’s fibre into this maze and then out again to residential and business premises is one hell of a fundamental construction job.

The ongoing delays have led the Tasmanian Government and others in the industry to propose what may, on the face of it, seem like something of a radical idea: Not to use Telstra’s infrastructure at all.

Tasmania has form in this area. The State Government’s TasCOLT project saw several thousand households in several metropolitan areas in the state receive aerial fibre deployments constructed by state-owned energy utility Aurora Energy in 2006 and 2007. According to a report published in 2008, the model was successful, and Tasmania gained key learnings from the deployment that would aid in future rollouts.

Now the state is proposing that that concept be extended throughout the NBN rollout in Tasmania, in an effort to ensure that it receives FTTP broadband across the state under the NBN, and not inferior FTTN options. It’s a model Tasmania has proposed before — back in 2007 and 2008, when Kevin Rudd’s first Labor administration was examining a nationwide FTTN rollout in partnership with industry, as the first NBN plan. And now it’s back.

The thing which NBN Co’s team of executives, analysts and consultants needs to realise when considering the aerial FTTP model, as compared with the underground FTTP model which it has largely been pursuing so far, is that the model makes a hell of a lot of sense not just for Tasmania, but for the wider national NBN rollout in general.

It’s worth considering that in many ways, deploying telecommunications cables under the ground is actually something of an anomaly when it comes to Australian network rollouts — and especially in the last mile to actual premises.

Sure, Telstra’s copper cables are primarily under the ground now, but initially they were mostly deployed on telegraph poles between cities and then in neighbourhoods. Over the last century they have gradually migrated underground, but it’s taken a long time for that to happen. When Optus deployed its HFC cable network around metro areas in the late 1990’s, it did so in the air on power poles. Telstra initially wanted to put its HFC cables underground but eventually followed Optus as it found it hard to keep up with its rival’s aerial fibre deployment.

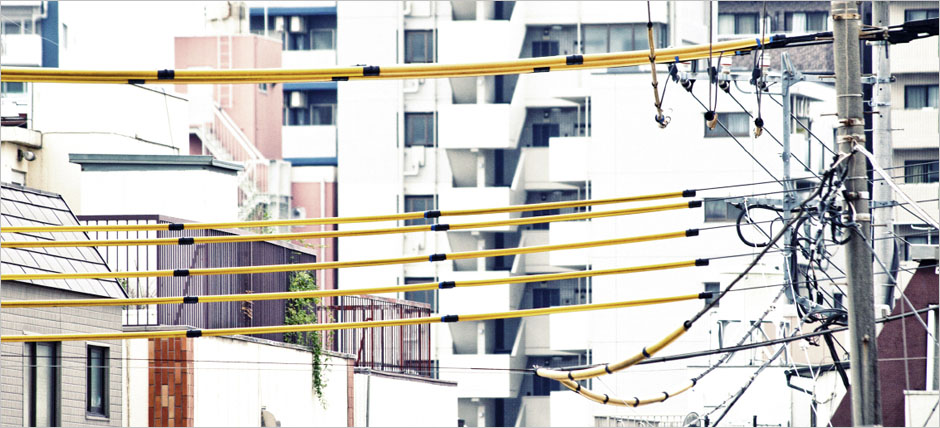

The same can be said of other countries. Japan, for instance, known as one having one of the best broadband networks globally (actually, it has quite a few), has deployed most of its FTTP cables aerially. And similar examples can be found around the globe.

The benefits of deploying fibre aerially rather than underground are quite obvious. According to a report prepared for Malcolm Turnbull by Aurora in Tasmania, the cost can be substantially cheaper than deploying fibre underground, and aerial networks can also be significantly faster to deploy. Both of these factors are major issues for the NBN which the Coalition is seeking to address.

Another thing to realise is that the NBN is already being rolled out aerially in many areas. Around 25 percent of the network’s fibre build is slated to take place in rural or regional areas where underground ducts do not exist — the existing copper cabling is literally buried under metres of dirt. You can’t push optic cable through dirt, and it’s too expensive to build new ducts, so NBN Co is already planning to deploy a large slice of its network aerially.

NBN Co has also already negotiated, or forced its way into, relationships with power companies around Australia where it is already deploying some fibre aerially in areas where it is deemed too expensive to deploy its fibre underground.

And, of course, there is also the fact that deploying aerial fibre cables will usually not require NBN Co to do much construction work to deploy fibre from the street to premises, as the new cables will usually be able to enter through the same point as the existing power cables. You can see a detailed photographic article detailing how this process works in Japan here.

The downsides of aerial cable are, to put it bluntly, extremely manageable.

Critics of aerial fibre often link to photos of Japan’s streets criss-crossed with fibre ables and highlight the fact that the cables are ugly. However, what many Australians don’t realise is that these aren’t just telecommunications cables we’re looking at in Japan — there’s a stack of other cables there. Fibre, HFC, power, copper, etc. Australian streets are never going to be that crowded.

As evidence for this fact, look out your window right now, if you live in a metro area in Australia. You probably already have poles in your street with aerial electrical cables and HFC cables from Telstra and Optus on the same poles. But few people ever complain.

One more aerial fibre cable added to the mix will, as the TasCOLT situation in Tasmania conclusively proved, make very little difference to the situation. Today’s optical fibre cables are light and unobtrusive. They’ll blend in well with the existing mix. It’s even possible that the shutdown of the HFC cable networks associated with the NBN will even result in some of those other aerial cables being removed, improving the view further.

Other potential issues with aerial fibre include higher maintenance costs because the cables are exposed to problems like trees falling on them in storms, being burnt by bushfires and so on. However, given that these same problems are dealt with satisfactorily by electricity utilities with their cables, it’s hard to see this being a huge issue.

In the long run, of course, as with the copper, you would expect to see more and optical fibre cables migrate underground. This is precisely what happened with the copper and backhaul fibre networks, and you’d expect to see it with fibre access networks as well. The removal of Telstra’s copper from its ducts (after the fibre is laid aerially) will make this process even easier.

One significant caveat to all of this is that the aerial fibre model really only works with FTTP rollouts or FTTP deployments. The nature of FTTN deployments, depending on streetside ‘cabiners’ or ‘nodes’ as they do, as well as on existing copper lines, means the aerial fibre model does not mesh as well with the FTTN deployment option as it does with FTTP or FTTB deployments.

Of course, I’m simplifying things drastically here. Not all power cables are above ground now — aerial cables are not already used in many areas of Australia, and each street and neighbourhood will still need to be evaluated separately to determine whether the aerial or underground route is the most appropriate one to take. But what I am arguing for is for NBN Co to consider, in its strategic review, the case for increasing the proportion of its FTTP network rollout that takes place aerially, as opposed to underground.

When Communications Minister Malcolm Turnbull published the Coalition’s new Statement of Expectations to NBN Co in late September, the MP stated:

“The goal of the strategic review, as you know, is to ascertain what it will really cost in dollars, what it will really take in years and months, to complete the project on the current specifications. And then, to assess, what options there are to reduce that cost and time, by using different techniques, different technologies,” the Minister added.

“As you know, as everyone knows, we’ve canvassed an example of that in our policy document, but let me say again, as I said to NBN staff today, I am, and the Government is, thoroughly open-minded, we are not dogmatic about technology; technology is not an ideological issue. We are completely agnostic about it. What we want to do is get the best result for taxpayers as soon as possible.”

Telecommunications analyst Telecommunications analysts such as Paul Budde interpreted Turnbull’s policy backdown as the Minister having given NBN Co “the opportunity to save the current NBN”.

“For me the key issue was that the review that he has announced is, in his own words, ‘not dogmatic’. He has first of all asked NBN Co to review its operations with the aim of coming up with changes that will see lower costs and a faster rollout within the current parameters of the project, this being mainly an FttH rollout,” wrote Budde in a blog post at the time.

“It is now up to NBN Co to make changes to its plan that would allow it to continue the project, under the existing specifications but in a much more effective and efficient way. And, according to the experts I talk to, this is possible. NBN Co should therefore be able to come up with a better plan, based on the new situation that has presented itself to them under the new government … It is now up to NBN Co to show that it is indeed able to build as much as possible of the original NBN, cheaper and faster.”

Using FTTN is certainly one way of achieving many of NBN Co’s aims while reducing cost and time of the network’s deployment. But aerial FTTP is also another method towards those aims. This means NBN Co must consider it as an option in the company’s Strategic Review. Not to do so would mean criminally missing out on an invaluable opportunity to maintain many of Labor’s original aims for the NBN (aims the Australian public still supports) while injecting a solid and needed dose of Coalition pragmatism.

I’ve got aerial NBN at my house and it was very fast to install, both on the street and connecting to the house. The cable is so small that I didn’t even see it at first, I thought the guys were working on the power lines until the next day when I saw a big cable spool with corning written on the side. The cable is installed very high on the pole so its mostly out of view anyway.

Locally as I have mentioned the copper was Kaput, where there were no longer useable pairs to provide for all the dwellings. Telstra has replaced several hundred meters of underground with aerial as their pipes and ducts were full of old disconnected cables and the existing decaying one. Been a bit of that going on I notice. Other point is those clogged ducts and pipes can now be stripped as not carrying any active services.

No real improvement to my ADSL, now more random impulse noise spikes from electrical equipment, old cars etc knocking the service out

Interesting

PMG and early Telecom spent a fortune buiding their pipe, duct and pit infrastructure to shift the aerial cables underground to reduce maintenance costs. Now after corporitising and privatising, that effort and money has been wasted by poor management practises, back to the future.

The other issue of course apart from National communications infrastructure and National Security is the weather aspect.

Interesting show on SBS this week

http://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/program/958/Countdown-To-A-Catastrophe

Storms,

How viable long term is an aerial solution?, due to constant flexing I would expect plastic fibres rather than glass, so much shorter life span.

I was always concerned at the amount of aerial being used up North

interesting aside is the amount of gamma radiation emitted by lightning

Plastic fibres! Too much attenuation (loss of signal) FTTH routed underground is the most fullproof & future proof method, it would even mean that the fibre/coax hybrid network now strung all over metro areas could be dismantled as FTTH can carry the bandwidth required, a bit more blue sky for everyone!

Comments are closed.