This article is by Karl Schaffarczyk, law student at the University of Canberra. It first appeared on The Conversation and is replicated here with permission.

analysis “The NBN could have disastrous results for the local [music] industry.” At least, that was the view of peak recording industry body the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) and local bodies, the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) and Music Rights Australia, in a recent report.

But why would Australia’s National Broadband Network (NBN) be problematic? The Age, The Register and other media describe the claims of IFPI and ARIA as “bleating”. The joint claim of the recording industry bodies is that without government and internet service provider (ISP) intervention to curb piracy, the NBN will destroy the music industry.

But this is just business as usual for the content industry. These claims are continuing a long tradition of claiming every technological innovation spells disaster, if not the end, of the industry.

Some 30 years ago the then-Motion Picture Association of America president, Jack Valenti, described the VCR as the movie industry equivalent of the Boston Strangler. Even high-speed dubbing and blank tapes, digital audio tapes, Napster, Grokster and countless other technologies have been named as threats over the years. Despite these threats, the recording industry is still with us.

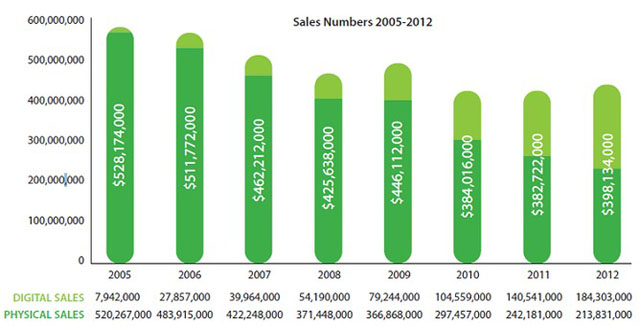

Not only is the recording industry still with us – in Australia, at least, it is doing well. IFPI and ARIA report impressively strong growth (up 40%) in Australian digital music sales, and a small increase in overall revenue. In an Australian context, the sales data in the graph below clearly shows that while sales of physical recordings are declining (dark green), those losses are being offset by the growth in sales of digital recordings.

IFPI’s annual Digital Music Report repeatedly advocates for legislative intervention from government to compel ISPs to better enforce copyright.

They want ISPs to become “content gatekeepers” by either preventing consumers using services that permit file-sharing, or implementing enforcement protocols such as the American six strikes Copyright Alert System, which warns (and then reduces the internet speeds for repeat offenders) users who engage in illegal file-sharing on the internet. Australian lawmakers have so far been reluctant to make this happen, and a major issue in the recent High Court case of Roadshow Films v iiNet was iiNet’s unwillingness to be the gatekeeper for Hollywood.

ARIA is now holding out for the current Law Reform Commission review of copyright and the digital economy to deliver a strong[er] copyright framework.

Alarmist claims about the NBN tell us more about the music industry and its attitude to consumers than any inherent faults in consumer behaviour. It is widely accepted that people download music and other content due to the failure of the market to deliver what the consumer wants. This failure takes the form of insisting that old business models such as selling CDs and tapes in discrete markets be continued – while refusing to embrace the new digital culture.

Granted, the marketplace for legally-downloadable music has developed over the last few years and we now have online music stores and streaming services, but until now the online offerings have been inferior in many ways. Saddled with Digital Rights Management (DRM), small repertoires and high prices, many people had instead resorted to file-sharing services.

The logic in the IFPI report is attractively simple: if people can download songs from the internet using peer-to-peer (P2P) networks, and those people are then given faster internet speeds as provided by the NBN, they will download much more music. More downloads means fewer sales, and fewer sales means disaster for music distributors.

While there will always be people who prefer to “freeload” and not pay for content, the impact of Apple’s iTunes store has demonstrated that many pirate downloaders will happily convert to paying customers, but that iTunes has a negligible impact for existing content purchasers. What this shows is that consumers want a simple interface from which they can pay for their music.

The music industry has long insisted on “digital locks” (“DRM”) to prevent the sharing of legally-bought digital music. But technological compatibility and digital rights management have also been a strong deterrent for consumers. Why pay for a song that only works on one or two music players? It has been shown that DRM-free content – such as songs which are sold without any form of digital lock to prevent file-sharing – actually drives sales.

Price is another important factor in consumer needs. For decades when buying technology, Australians have been paying higher prices than our overseas counterparts. This applies to online and offline music sales too. On Apple’s iTunes store, the standard price for one song is US$1.29 for Americans, yet the price for Australians is almost double that, at A$2.19 for the same song.

Timing and geographic segmentation is yet another issue for which the content industry fails to deliver to consumers. This is most obvious in the film industry, where Australians often need to wait months or years in some cases before a released film hits our screens. The music industry is not immune to this either, and it is still standard practice to release all but the biggest names in music one market at a time.

While it is a long bow to draw to claim that piracy will disappear if content became cheap, DRM-free, easy to buy, and simultaneously released worldwide, it is clear that these are important factors driving online piracy, and fixing these matters will significantly reduce demand for infringing product. If the music industry is scared of a piracy-driven disaster occurring because Australians have high-speed broadband, it means they believe the only thing saving their bacon is the lack of bandwidth available in most homes.

It also means that despite being aware of what drives music piracy, the industry intends to continue treating its customers with contempt. Frances Moore, CEO of IFPI, summed up industry attitude to consumers in last year’s Digital Music Report:

The truth is that record companies are building a successful digital music business in spite of the environment in which they operate, not because of it.

The time has come for the music industry to find common ground with consumers, not do business in spite of them.

Karl Schaffarczyk does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations. This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.

Image credit: Svilen Milev (author site), royalty free

![]()

you can download a song in 10 – 20 seconds already (if not less).. i doubt faster internet is going to make people want to download more songs.

Indeed, back in my day it would take 20 minutes to download one song from Napster. And we loved it! So quick and still faster than the time it took to encode the MP3 on my 486.

+1

It’ll be a disaster, but not for the industry, for record labels. We already live in a world where self distribution by artists is possible, the NBN will do nothing except further enable that for Australia artists.

The record labels may die, but the “industry” will stay very much alive.

Exactly, they are being alarmist not because the industry might die, but because they know that if the trend continues they won’t have a place in that industry.

Indeed. I’d say most people are limited by the time they have to spend looking up artists and queuing up downloads (and by that I mean they choose to only dedicate a certain amount of time to the endeavour, not that there is no more time in the day available). The time downloads themselves take to complete is essentially immaterial, as it has been pretty much since people moved away from dialup. Give people 1gb/s Internet and the only change it will make to their piracy habits (if they engage in them) is the quality of video they access (ie downloading 1080p HD which can occur within a reasonable time (such as 5 mins) rather than the hour or two it may take over ADSL-style broadband. They will still pirate the SAME shows as they do today, they will still pirate the same amount of music, because their time and interest level is a far more limiting factor (ergo the ‘bottleneck’) than their Internet connection bandwidth.

The NBN could be a boon to the music industry. Better, faster distribution of digital recordings. Higher quality recordings. Legal online music could be and should be big business – but the music industry wants to stay in the 20th century.

Of course, it doesn’t occur to the industry that part of the downturn in sales has been because it has tried to stop online distribution. Or perhaps because the music industry is too focussed on plaid as its product, and refuses to back original music? Certainly the last 15 years have produced some total rubbish – people like Cyndi Lauper, and perhaps even groups like Devo, just would not have made it in today’s industry. Too “different”.

Damn right, I think this will happen to the movie industry too, especially the live streaming. My wife loves her shows and if it isn’t on iview there’s really no other way to get it other than Foxtel.

We’ve tried streaming services with no luck, either we can’t sign up because we are in Australia or it’s just to damn slow!

Can’t access it because you are not in Australia?

You don’t try hard enough.

Read this: https://theconversation.edu.au/say-hola-to-the-newest-route-around-web-censorship-11845

and this:

https://theconversation.edu.au/so-whats-wrong-with-watching-the-olympic-games-over-the-internet-8704

Yeah I tried the VPN, works fine, still left with the same problem though… Buffering.. Buffering :(

They’re barking up the wrong tree. Their DRM is the sales killer as far as we’re concerned.

Our weekly media purchases came to a screeching halt years ago after getting burned by a number of expensive but crippled DRM protected disk albums that still remain unused to this day as we couldn’t extract the few desired tracks that prompted our purchase to our preferred medium.

Never again!

Interesting.

With high bandwidth available to every music consumer with the NBN, I envision a future where artists can stream live performances to many thousands of people across the country (or the world, once they catch up to Australia). Not quite a live concert, but the next best thing. These could be free or sponsored, supported by donations, supported by banner ads or ad breaks, or paid for a la concert tickets. I doubt this is an original idea, but something that will become much more accessible with the NBN.

Which is why, and lets get this straight, the Recording Industry and not the Music Industry hates it with a passion since their gate keeping role of being middlemen becomes more and more irrelevant and their power over artists (of all shapes and forms) becomes moot.

This doesn’t mean the Managers and promoters wont be affected, far from it since I can envisage them having an even greater role to play though they might have to work a bit harder for their percentage cut (which is NOT a bad thing).

“It is widely accepted that people download music and other content due to the failure of the market to deliver what the consumer wants.”

+1000

I don’t use itunes or any other online music store. I still buy CDs from Amazon, wait for them to be delivered, rip them to FLACs and upload them to Google Music so I can stream lower quality music to the car and have higher quality music in the house. The fact that I get higher quality, lossless, drm-free music and that this is the cheapest way to buy music in 2013 is a sure sign the music industry is completely bat-shit insane.

And don’t get me started on the movie industry. If I buy a blu-ray why can’t I down-convert it for use on a tablet or get free access to it from a cloud service like Google movies?

I don’t personally pirate but the music and movie industries have brought it on themselves. Stop automatically assuming your customers are criminals which is all drm actually is.

exactly. i notice today Foxtel is crying poor in the FinRev

http://www.afr.com/p/technology/foxtel_ceo_calls_for_government_tsznMogO9vEMTGny6RutjP

but they ignore that their freshly released service will reduce piracy – given people with net access can now legally get at Game of Thrones – and that will have a far bigger effect on the market than any legislative instrument such as ‘6 strike’ and the like. 6strikes is actually looking a tad shaky in the US, as more and more judges make comments and rulings that an IP address is not sufficient to pin something on someone.

just on GoT itself ‘the most pirated item’ in Australia, now having a legal route to viewing would probably make a large dent in local piracy rates. let alone all the other cable content we’ve not been able to access without the HFC out the front door (or a sat dish, but i understand that is a smaller set of users). the govt actually doesnt need to lift a finger at all (isnt that what conservatives seem to constantly say – govt doesnt need to be involved in this that or the other?) to achieve the result the industry is most concerned about – more bucks in their pockets.

if Foxtel had in the past less of a bent on getting government to write law to their tastes, and done more on releasing this product the ‘failure’ of the market would not nearly be as big a problem as theyve made it out to be. and theyd have been making bucks earlier to boot. the failure is yours: you did it to yourselves, fellas. take some responsibility.

Focussing on GoT here, but it applies to plenty of other media. When you hide a popular item behind two paywalls (TWO!!! Basic Foxtel, plus Showtime) then its only going to encourage people to look for alternatives.

And those alternatives have no barriers to access, apart from the time it takes to source them, and download them. The world has changed, and the entertainment industry is being dragged kicking and screaming into this changed world.

The music industry went through it over the past 10 years, after Napster showed the way for iTunes to capitalise on. Fast forward to today, the industry hypocritially shouts to the world about how proactive they were moving to the digital era…

Movie and TV industries are walking the same road.

I gave up p2p downloading of any music content once Spotify came to Australia. Prior to that I selectively purchased through iTunes and CDs for my must-have purchases and dodgy downloaded the rest. Either way, my paid Spotify subscription ensures I spend more now than I ever did on music.

One insight I got from my own impulsive behaviour was that Spotify and services like that are probably the future for most music, and that they redistribute income fairer than traditional digital and physical sales models. In the traditional model all but the most avid collectors would only purchase a small number of CDs benefiting mostly about 1% of artists – the top 1%. This is reinforced by royalties from radio and other sources that probably just serve to increase the gap between the top 1% and everyone else. Streaming on demand services mean that smaller bands are more likely to get at least some payment (if only small) as the ability to listen to anything means you’re more likely to move outside the confort of the 1%.

The downloading culture will get broken by services like Spotify, the challenge is to find the right mix of models between free and paid services to match the different markets.

Yay, the NBN will allow me to download a movie in 5 minutes instead of 10 minutes.

More music/film industry hysteria.

Personally I’m looking forward to live streaming of concerts in FullHD.

The ‘International Federation of the *Phonographic* Industry’ expects to be taken seriously in the 21st Century? Jeez, I grew a bustle on my ass just reading their name…

The only thing that is at risk under NBN is the industries current business model, and control. Control means money. When everyone is free to distribute and sell their work, outside of the business, you shift where the money goes (primarily to those whom are the source of the content).

The industry that has been built to control and massively profit from the flow of content is deathly afraid that they will become irrelevant. The times are a-changing.

Indeed, back in my day it would take 20 minutes to download one song from Napster. And we loved it! So quick and still faster than the time it took to encode the MP3 on my 486.

This TED talk is so relevant.

http://mirror.aarnet.edu.au/pub/TED-talks/AmandaPalmer_2013-480p.mp4

+1. Good talk.

Comments are closed.